2 Yields

There has been much to make of this year’s yield curve inversion.

And by “yield curve inversion” I actually mean “YIELD CURVE INVERSION!!!!!!” As those on TV tend to refer to it.

As a quick refresher, the yield curve is a graphical representation of how much interest (yield) a bond produces based on the length of maturity on that bond. Think of it this way:

Your oddball cousin Eddie wants to borrow some money. You agree.

If he pays you back next month you don’t feel the need to charge him a high interest rate.

If he wants to pay you back two years from now you’ll likely want a bit more interest because you’re giving up access to your dollars for longer.

If he wants to pay you back ten years from now you’ll want an even higher interest rate because there’s a pretty good chance that within ten years cousin Eddie moves to the mountains, goes off the grid, and never pays you back. You want to be compensated for that risk.

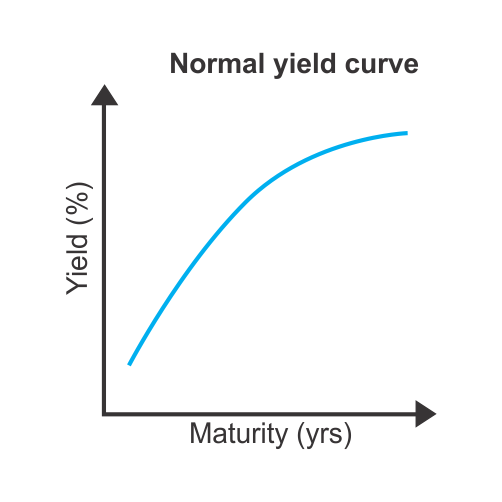

This natural desire to want more return (yield) from loaning money for longer periods of time leads to a normal yield curve which looks like this:

When investors decide to ditch short term bonds (driving their price down and their yields up) in favor of longer term bonds (driving their prices up and yields down), this relationship becomes inverted. This simply means new investors get less interest for buying longer term bonds than they do shorter term bonds — which discourages them from making long term investments. Lack of long term investment is bad for the economy and is one of the reasons why yield curve inversion tends to be a recession indicator.

Ok, enough on the yield curve. Let’s talk about traffic.

Remember this sign? Oh you don’t? You probably just drove past one while you were rushing home to read this blog. No worries.

Yield, in traffic, means let other cars go first. Unlike with stop signs, drivers aren't required to come to a complete stop at a yield sign and may proceed without stopping -- provided that it is safe to do so.

Just like yielding in traffic, many investors have been yielding to the Fed’s action, then determining a path forward once it’s safe to do so.

Here are a couple paths based on the Fed’s recent actions to raise rates.

Path #1 - Better Yields on Safer Stuff

In light of recession fears and inflation problems, one thing many investors have forgotten about higher interest rates is that the interest rates on stuff will become, you know, higher — newly issued bonds pay more and the return on your savings account at the bank will hopefully no longer be nine pennies per year (or whatever it was).

Recently I’ve been watching money market rates pretty closely. In particular, I’ve kept an eye on this fund we can buy at Schwab & Altruist:

Schwab Value Advantage Money Fund® - Investor Shares: https://www.schwabassetmanagement.com/products/swvxx

(To be clear, this blog is never an endorsement of a product. I am simply using this fund as a real world example of some of the options investors have.)

As of right now, this money market fund has a 7-day SEC yield of 2.22%/yr, which is considerably higher than the returns these kinds of funds produced at the beginning of 2022.

Thinking back to the inverted yield curve discussion above, keep in mind that 10 year treasury bonds are paying about 3.3% as of this week. This money market fund is a little like a 30 day bond (the average maturity of a loan in SWVXX is about 60 days). So while this particular relationship is not inverted (the 10 year bond pays more at 3.3% than the money market fund does at 2.2%), you have to ask yourself “is an additional 1.1%/yr worth it for buying a 10 year investment? Or is there something better we can do with our money if we are okay leaving it alone for 10 years?”

Simply put, investors can start to hold their cash in different ways to try and get a bit more return out of their portfolios, but that is not their only path.

Path #2 - Less-Safe Stuff

As we mentioned above, yield curve inversion tends to be a good indicator of a recession. But many stocks have already fallen this year in advance of any data to suggest the recession has arrived. This is because current prices tend to reflect future expectations.

I’m not a big advocate of buying individual stocks as a way to drive alpha (i.e. “beat the market”). It’s just really hard to do and few can do it consistently. But I’m always okay with people owning stocks because they like a few companies and want to own stock in them. After all, when things get choppy (as they currently are), it’s important to have a story you believe in. Some find it easier to attach themselves to a story when it’s built around individual companies — I get that.

In the spirit of building a story around a few individual companies, here is an observation:

Remember the 2.22% yield currently being paid by the Schwab Money Market fund?

Here are some stocks currently paying about the same amount in the form of dividends:

McDonalds — 2.17%

General Dynamics — 2.18%

Union Pacific — 2.21%

Qualcomm — 2.23%

Jack In The Box — 2.18%

… Unlike the money market fund which has not declined in value this year, each of these stocks (aside from General Dynamics) is at a loss year to date.

Here is the YTD performance of each company (through 9/5/22):

McDonalds — 3.47% loss

General Dynamics — 9.66% gain

Union Pacific — 9.64% loss

Qualcomm — 28.68% loss

Jack In The Box — 6.12% loss

Those losses are tough, but here are the 10 year annualized rates of total return (total return = dividends plus price appreciation) for each of these companies:

McDonalds — 14.14%/yr

General Dynamics — 15.74%/yr

Union Pacific — 16.40%/yr

Qualcomm — 10.77%/yr

Jack In The Box — 13.55%/yr

*Past performance is not indicative of future returns.

Again, I don’t advocate for individual stocks, but I use this example because I want you to evaluate the difference between the yield-only prospects of the safe money market investments and compare them to the dividend yield plus/minus the growth or decline of a stock.

If you can attach yourself to a story about Big Macs, defense spending, railroads, telecom, or fast food, and ride that story through the ups and downs of a volatile stock market, then you might be better off going with a riskier approach. Of course, I would personally pursue a fund-based, more diversified approach than any of these individual stocks, but the principle remains the same: if the yield is comparable between cash and stocks, how much confidence do you have in the ability for stocks to grow over the long term?

I am always pro-growth, but you’ve gotta come up with a story of your own and, in this environment, you have several choices in addition to these two paths above — you just have to come up with something you believe in and can ride out through the storm.

That’s all for now.

Onward,

Adam Harding, CFP

*Not investment advice. Source data: Ycharts. For educational purposes only.