Coronavirus Response

The world is watching with concern the spread of the new coronavirus. The uncertainty is being felt around the globe, and it is unsettling on a human level as well as from the perspective of how markets respond.

The email below contains some data about declines and how we'll look to handle these conditions.

But first, a quick story:

This weekend my wife, Mollie, and I attended a wedding in Austin, TX; it was our first trip without our son, Clayton (thanks, grandparents, for watching him).

Like most new parents, we spent the entire trip looking at photos of him (like the one at the bottom of this email) with so much appreciation for the place we're at in our lives and looking forward to getting back home to him.... But in the back of my mind there was also a sense that we have a lot to lose if something were to happen to us.

On the return flight yesterday morning there was A LOT of turbulence. At the beginning of the flight they mentioned that it looked like it would be "a bumpy ride" but that they'd do their best to find smooth air. Smooth air was not found.

You know the place your mind goes to when there's turbulence like that --it's not a good place to be but you can't help your thought process.... And with being away from our son, the train-of-thought only gets more distressing.

But through it all, I relied on the captain's training and expertise to get us home safely. I didn't try to take over the controls, I let him be the expert.

This is oddly apropos for the place we find ourselves in today. Turbulence is here and it's normal, but so is the human response. Just hold on tight and trust us to be your advisor while we work through this.

My first job is to help separate emotion from strategy. It's easy to forget, but we planned for this kind of market shock during our initial discussions and we knew there might be some bumps along the way. We didn't know when it would occur, but the shock could've been geopolitical, systemic, etc. This just happened to be the pandemicshock that nobody predicted (okay, well maybe one person predicted it and is now loudly advertising their fortune-telling acumen. Ignore that person.)

At my firm it is a fundamental principle that markets are designed to handle uncertainty, processing information in real-time as it becomes available. We see this happening when markets decline sharply, as they have recently, as well as when they rise. Such declines can be distressing to any investor, but they are also a demonstration that the market is functioning as we would expect.

Market declines can occur when investors are forced to reassess expectations for the future. The expansion of the outbreak is causing worry among governments, companies, and individuals about the impact on the global economy. Apple announced earlier this month that it expected revenue to take a hit from problems making and selling products in China. Australia’s prime minister has said the virus will likely become a global pandemic, and other officials there warned of a serious blow to the country’s economy. Airlines are preparing for the toll it will take on travel. And these are just a few examples of how the impact of the coronavirus is being assessed.

The market is clearly responding to new information as it becomes known, but the market is pricing in unknowns, too. As risk increases during a time of heightened uncertainty, so do the returns investors demand for bearing that risk, which pushes prices lower. Our investing approach is based on the principle that prices are set to deliver positive future expected returns for holding risky assets.

We can’t tell you when things will turn or by how much, but our expectation is that bearing today’s risk will be compensated with positive expected returns. That’s been a lesson of past health crises, such as the Ebola and swine-flu outbreaks earlier this century, and of market disruptions, such as the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. Additionally, history has shown no reliable way to identify a market peak or bottom. These beliefs argue against making market moves based on fear or speculation, even as difficult and traumatic events transpire.

Still, we know that these events are normal. Here's how frequently we see drops in the market:

So that puts this current decline at about a once-every-four-years kind of drop.

But what about pandemic-specific drops?

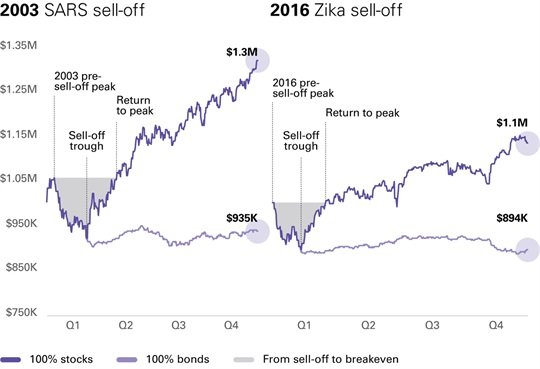

While they’re not exactly the same, stock market reactions to the SARS in 2003 and the Zika virus in 2016 can offer useful lessons. In both of these cases, investors who sold on bad news missed significant rallies that very shortly had stock markets back to pre-crisis levels.

Here's an illustration of those two markets:

There’s no guarantee that today’s market will play out the same way; stocks have also taken days, months or longer to regain losses. But remember that knowing when to get back in is just as hard as knowing when to get out. The investment strategy I’ve mapped out for you is a long-term plan based on your personal goals and circumstances.

Here's a longer-term look at how the markets have reacted in response to various health-related issues:

For a bit of context:

2003 — SARS saw 8,000 people infected. It was brought to an end by good hygiene (hand-washing) and environmental factors (warming temperatures), and it burnt out when enough people became infected to build an immunity to the disease.

2009 — H1N1 Flu caused a pandemic in ‘09 and has become a seasonal flu, usually recurring in the colder months.

2014 — Ebola in West Africa ended with human intervention, when the WHO declared a coordinated international response. Countries worked together to administer to the sick, and when a second outbreak occurred in 2018, human intervention made the difference again when treatments developed from the first outbreak were offered to patients.

Here's what I think....

I once worked at a firm where market conditions like this would warrant an "all-hands-on-deck" meeting to discuss "doing something" because there was a belief that our clients expect us to know what's going to happen in the short run... I would never have you believe that. It was during those meetings that something became clear to me:

Behavioral finance applies to all humans; including financial advisors.

Situations like this cause people to feel like they need to “do something” and you should be concerned if your advisor is deviating from their plan.

The only thing that makes any sense in these environments is to put current activity into the context of the bigger picture and to acknowledge that biases can affect our thinking. These factors may lead investors to believe that markets are doing worse or better than impartial analysis would reveal:

Confirmation bias: Giving more weight to trends you already believe in (i.e. If we think it will get worse, then the news suggesting it will get worse is where our eyeballs go)

Availability bias: Giving more weight to recent events (also called "recency bias"). Three months ago everyone believed the economic expansion would continue in 2020. Now everyone believes the decline will continue indefinitely.

Framing effect: Letting the presentation of information affect your interpretation of it (i.e. Where do we get our news? Does a more subdued story-line attract more or less eyeballs which can be used to generate advertising revenue?, etc.)

But in times of volatile markets, the best move of all for long-term investors is often no move at all.

I know that "do nothing" sounds like zero fun and it doesn't ease your fears. But here's what I actually mean by "do nothing".... stick to the plan you already have in place.

This plan should account for volatility in a few ways:

1) If you're aggressively invested then you're likely seeing wild swings in the value of your portfolio. You should only be aggressively invested if you have time on your side or if you're still contributingto your portfolio. If you have time then the current volatility is likely to fade into history and become an afterthought. If you are still contributing then your cash deposits should be buying shares at a lower price than just a couple months ago.

Keep in mind that even a portion of your portfolio should be aggressively invested in your 60s, 70s, 80s, etc... People are living longer than ever and all of us have time on our side for at least some of our investments.

2) In taxable accounts we need to keep a sharp eye out for tax-loss harvesting opportunities. Here's how it works:

We buy a diversified portfolio and expect that everything we own will be worth more over time.... Notice how I said "over time" and not "all the time".

When things we own decline in value in the short run, we can sell the investment that's declined and capture (harvest) the loss on paper to help offset a future capital gain or a certain amount of our income.We don't know when the rebound will occur so we need to buy that replacement fund immediately. The replacement fund must be sufficiently different than the original fund in order to meet the IRS requirements, but that's relatively easy to accomplish.

For example, let's say you buy an S&P 500 Index fund with $50,000 and you lose 10% in a week. You can sell at a 10% loss (-$5,000) and immediately buy an S&P 500 Value or S&P 500 Growth fund with the remaining $45,000. Then this loss you recognized can help offset a taxable gain or income in the future.

*This is not a recommendation for any of these funds. Just an example.

3) Rebalancing. Many clients will see trades this week as a result of us rebalancing their portfolio. In the more moderate and conservative strategies we run, we purposely own holdings with lower long term expected return than stocks. They have kept you from making higher returns (like those of the stock market in recent years) because we own them for one reason: to hold up better than stocks in markets exactly like this.

Simply put, if we don't sell bonds and money market funds in order to buy stocks after a 15% decline (or more), then why own the bonds in the first place if their long run rates of return are lower than stocks? We have to stay disciplined and true to a plan.

4) Taking advantage of lower interest rates. As the flood to safety has pushed interest rates to new all-time lows (interest rates fall when bond prices rise. Bond prices rise when demand for them is high. Investor fear = high demand).

If you have mortgage debt, consider the potential impact of refinancing.

If you have home equity and also other kinds of debt (car loans, credit cards, student loans, etc.) then consider the potential impact of refinancing, pulling some cash out of your home, and using that cash to pay off (consolidate) your debt at these low rates. My only requirement in this case is that you then subsequently redirect what you had been paying to the newly paid off debt and and send it to your portfolio or against your mortgage.

These are unique times with unique circumstances, but so was every other historical instance of something similar. Time passes and we forget that historical things were scary at the time, but they were.

We know that past performance is not an indicator of future performance, but we also must know that the practice of predicting something that has no historical precedence is unlikely to produce a favorable outcome.

During these crazy markets it can be helpful to chat. I've spoken to many clients and I encourage you to just drop a meeting on my calendar to review how we're doing, what our plan is, and how it's being implemented.

That's all for now.

Onward,

Adam Harding, CFP

Owner & Advisor @ Harding Investments & Planning

Data Sources for content above: Capital Group and Dimensional Fund Advisors