Gambling

Back in college I lived in a fraternity for a couple years — we had a poker table where myself and a few friends would gather around to play Texas Hold ‘Em (poker).

Here’s how it might go:

I sit at the table with friends and we each exchange twenty dollars for some chips. Remember, this is about 20 years ago and we’re all broke college students — this is a lot of money.

We set the blinds for $0.25 and $0.50.

We play for a while. If someone wants to be aggressive they raise a buck or two or three. A couple bucks might be enough to bluff the other players into folding their hand unless they have something good.

If someone loses all of their chips they can buy back in. Or they might just walk away.

Eventually the game ends when one person has all of the chips or the remaining players agree to stop and take their winnings.

The games were fun, but we really didn’t want to lose. The truth is, we couldn’t afford to lose that money; and the fact that we couldn’t afford to lose money is what kept us from betting more than a buck or two. It’s what kept us conservative.

Enter, my dad.

I distinctly remember this one time when my dad came to visit and he sat down to play poker with us. He was aware of how broke we all were — and since he was playing with money he didn’t really need — while we were playing on the razor-thin budgets of college students — he decided in advance that he was going to try to lose his chips to us.

Here’s how it went:

First, he played every hand. The worst starting hands in poker are 2-7, 2-8, 3-8, 3-7, and 2-6. He played all of them whereas most players fold these hands. Counterintuitively, this gave him a weird advantage because no one expected him to have these cards. Normally you wouldn’t expect a player to have pairs of 2s or 3s, so when it happens it can catch players off guard.

Next, he would purposely try to bet a few dollars even if he had bad cards because he wanted to lose more of his money to us. But when he raised it would often unintentionally scare the other players into folding.

In some cases, one of my friends tried to bluff by betting $5 to try to get my dad to fold his cards. Dad wanted to lose so he called the bet. My friend had nothing, dad had something slightly better than nothing. Dad wins.

When the round was finished, he had accidentally had done the thing he was deliberately trying not to do — he won.

When he left I think he gave his chips to the table to split up, but that’s not the lesson here.

The lesson is this:

When you play games with money you can’t afford to lose, you are far more likely to do exactly that.

When you play games with money you don’t specifically need, the odds of a successful outcome are in your favor.

So you might be thinking, “But Adam, investing feels like gambling and I need all of my money. I can’t afford to lose any of it.”

I’m sorry, but that’s just not true. You don’t need all of your money….But let me define “You” so I can be a bit more clear.

You = the person you are today and your needs, your wants, and current reality.

You’re right. Current You needs money and can’t afford to lose. You have a mortgage payment next month and groceries to buy this weekend. Current You can’t afford to gamble and play risky games.

But there’s another person in your life who has a vested interest in your money. This person is Future You. Again, I’ll define “Future You” for clarity’s sake.

Future You = the person you are in the future, their needs, their wants, and their desired future state.

…Future You can afford to lose money today.

…Future You can take risks Current You cannot.

…Future You may have needs which requires Current You to take uncomfortable actions.

When considering the investment strategy someone should adopt, the main factors to consider are purpose, timeline, comfort with risk, and capacity to handle risk.

Purpose is important because you can gamble a little more when the purpose is a want vs. a need.

Timeline is important because you can gamble a little more if you have time on your side.

Comfort with risk is important because we don’t want fear to drive investment decisions.

Capacity for risk is important because we don’t want greed to push us into taking risks we shouldn’t be taking.

Or Current You may have more money than you’ll need, so you’re able to invest for people other than yourself.

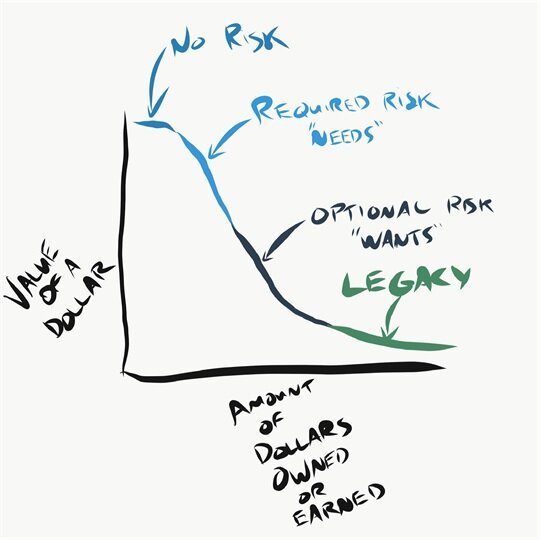

At some point you have to assign dollars a value based on what they provide to you today. The dollars in excess of what you need in the short run can be invested for what you may need in the future. And those in excess of what you may need in the future may contribute to the legacy you leave.

This is the basis of strategy.

Sketch from my blog post “One Hundred Million Dollars”)

The above sketch highlights this simple truth: the less an investor needs dollars, the more risk they can take.

…And when investors take reasonable and thoughtful risks, more potential return may follow.

…And more potential return can lead to more dollars they don’t need.

Then the cycle repeats.

Of course, there are smart ways (like thoughtful portfolio design) and reckless ways (like actual gambling or buying lottery tickets) to risk dollars, but none of it is possible without setting aside some funds you don’t need today.

With that I’ll leave you with one final observation.

Over the last 10 years we’ve seen a 21.99% drop in the real value of a US dollar (via inflation-adjusted US CPI).

There is a pretty good case to be made that the next 10 years will see an even greater erosion of the dollar’s purchasing power.

You’ve gotta give yourself a fighting chance to keep up — the only way to do that is to convince Current You to invest wisely for Future You. Doing nothing is a gamble you might not be able to take.

That’s all for today.

Onward,

Adam Harding, CFP | CEO and Advisor